An Approach to Understanding Meaningful Stories in Developing Countries

In the fall of 2018, I traveled to Accra, Ghana, to train 45+ monitoring and evaluation professionals (data geeks) working in the health sector.

The participants, mostly Ghanaians with a few ex-pats mixed in, came from more than 13 different international development partners and sub-grantees of USAID. We were also fortunate to have USAID Mission staff attend and get a chance to get their hands dirty working with the participants.

Infographic design workshop attendees in Accra, Ghana, proudly hold up hand-crafted work.

Infographic design workshop attendees in Accra, Ghana, proudly hold up hand-crafted work.

Conducting in-person workshops always brings out the TV producer in me. Interviewing a subject creates the opportunity to find the unique spark within someone.

Similarly, a participatory workshop that empowers people to become the producer of their own stories focuses on finding that same spark and fanning it into a roaring flame.

In this case, I went to Ghana to remind a group of professionals that we all have a creative spark inside of us, tapped or untapped, and to use it to translate international development stories into engaging infographics.

The audience was not made up of professional graphic designers, and admittedly had varying degrees of artistic skill, so I kept the focus on storytelling.

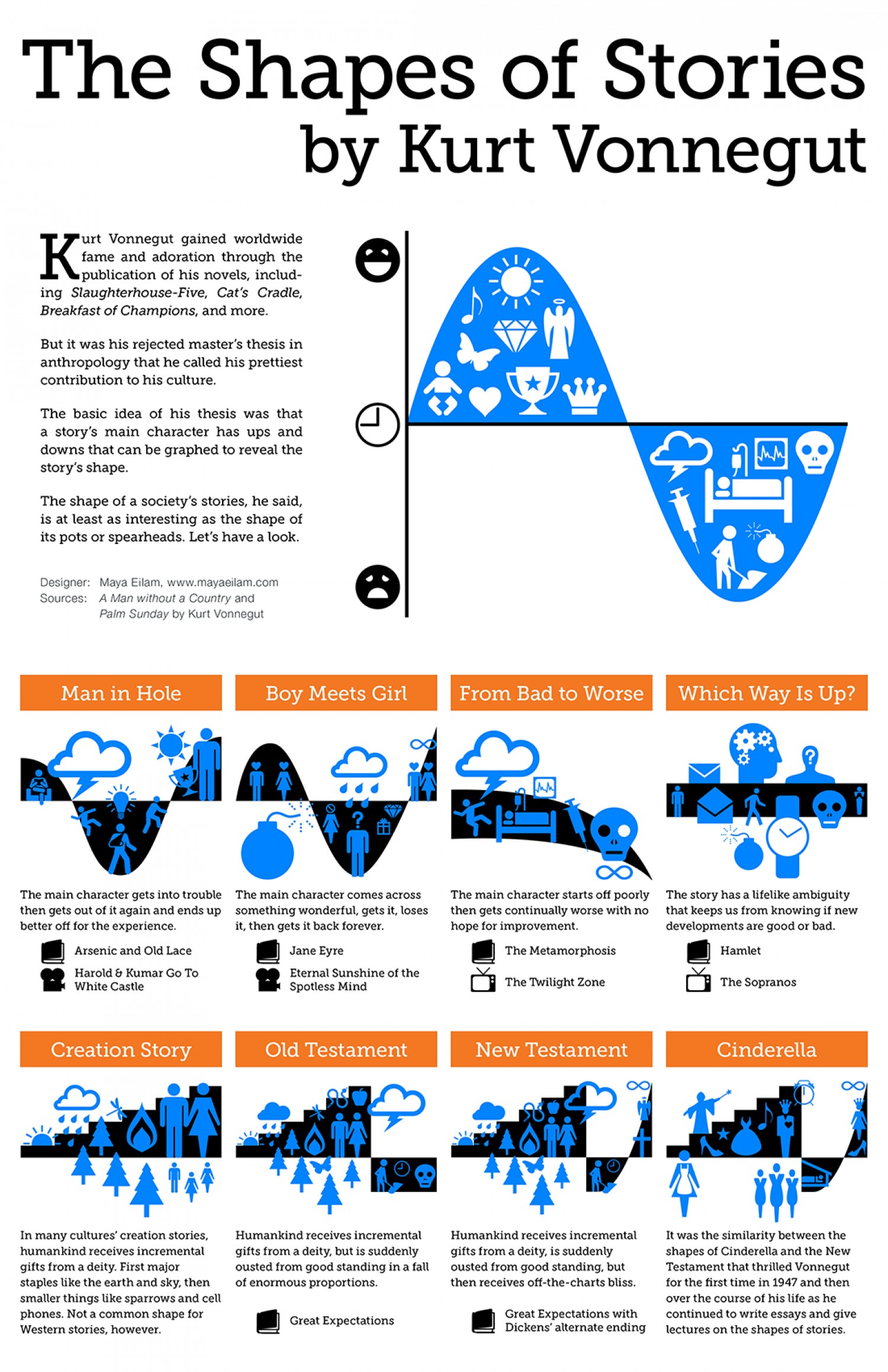

I chose one of my favorite storytelling reference tools, Kurt Vonnegut’s Shape of Stories, to introduce his classic theory detailing the eight archetypal story types.

His theory presents an effective framework to analyze story structure, and it’s just good fun to sit around college lectures debating which of Vonnegut’s model fits the latest blockbuster films, which I most certainly did.

His graphs are easily understood visuals that simply graphs stories on a x axis representing time from the beginning to the end of a story, and a y axis representing whether things are good (up) or bad (down) in the story.

Graphic designer Maya Eilam’s creatively reimagined Vonnegut’s shapes in a popular graphic used often to illustrate Vonnegut’s theory. I also used this image in my workshop in Ghana to help the groups’ understanding of what infographics are and how to think about each of their own project’s stories.

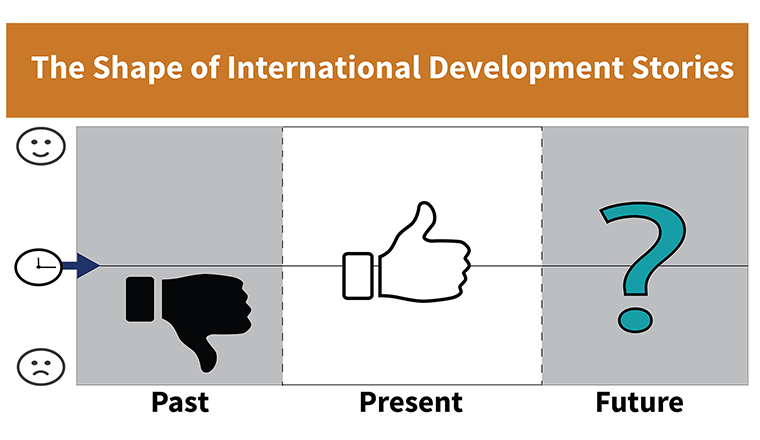

Although I’ve seen Vonnegut’s approach used in the international development context a few times – and it certainly helped those in my workshop to think through their infographics and identify a story – I couldn’t shake the feeling that the model wasn’t sufficient for international development story telling.

On my long flight back to Washington, DC, I began to think through MSI’s projects and how we tell our development story – a story I’ve had a strong role in telling for the greater part of the last decade.

My conclusion was that the disparity between stories and the story of an international development projects can simply be defined as “reality.”

What I mean is that story structure is very logical.

What happens before the story starts, commonly known as the backstory, is actually a question that all creation stories try to answer. This question is, “why are things the way they are?” or to get existential, “why are we here?”

Similarly, the “end” of story is the neat conclusion, at which point the universe ceases to exist, except in our imaginations, or the sequel.

In the real world, the past is often quite illogical and unrelated to the present. It may be unclear and complex how the past relates to the present.

And the future holds no guarantee of happiness, is certainly not “forever after,” and largely depends on a host of unforeseen variables.

In real life, there is no single, foregone conclusion or ending, but rather many possibilities in the future.

By contrast, development looks at current challenges (inherited from the past) and sustainability of the progress made through donor-assisted programs or possible back-sliding (the future).

Development stories rely on interpretations of the past, and theories of change that may or may not achieve various alternate visions of the future. For instance, in a post-conflict reconciliation scenario, there may be disagreement between communities about even the most fundamental issues, like which side is to blame for the conflict.

Based on extensive analysis, planning, and working with local actors, development experts make their best efforts to identify the issues and themes that can bridge differences between groups, with no guarantee of success, and many different ways it could manifest or fail. Due to constant real world issues and the evolution of a project, we build feedback loops into development processes to stay on the path to success.

Collaboration, learning and adaptation (CLA) is an approach we use that describes how we constantly work with every involved party that we can to learn from what we’re doing and improve upon our results.

So, development isn’t as cut and dry as one of Vonnegut’s models.

But I thought it was a worthy endeavor to try to adapt Vonnegut’s model and build upon Eilam’s designs, to apply the model to the The Shape of International Development Stories.

The following models do not represent the plurality and complexity of today’s development challenges and stories, but rather simplified visualizations of development themes or project objectives, to which MSI applies its services.

I hope these models help you think through the realistic challenges of telling your organization’s story.

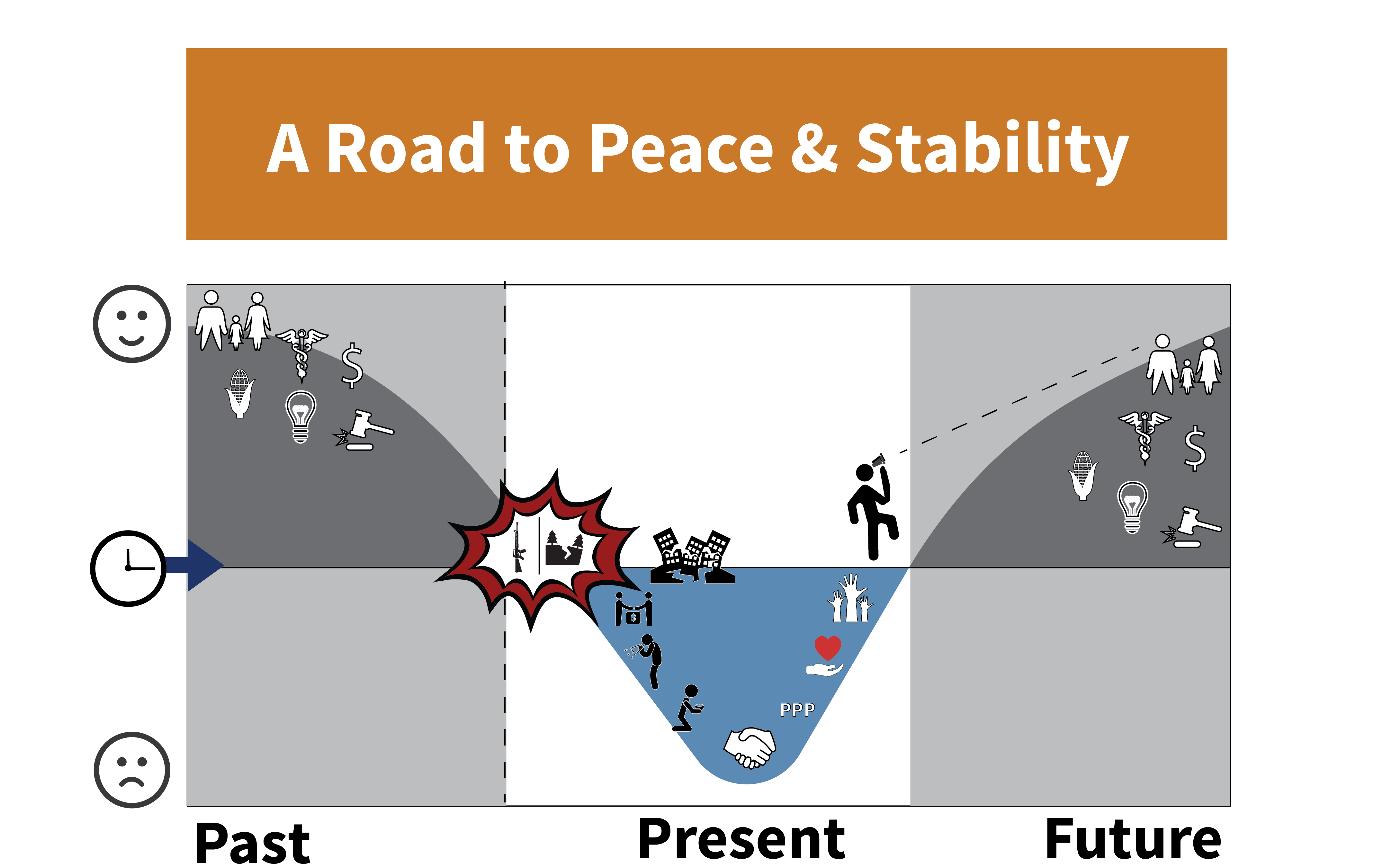

A country has suffered a decline, from good times to bad. Whereas the country used to have public services, decent schools and roads, a functioning justice system, an abundance of food, and peace, a recent violent conflict, environmental disaster, or other trigger, has precipitated a conflict.

The conflict impacts society on many levels – damaged infrastructure, poverty, disease, and inadequate services ranging from healthcare to sanitation.

Corruption thrives, benefitting those with power, money, and influence.

Through donor-funded programs focused on reconciliation, building public trust, igniting local participation, and building public private partnerships, citizens, government, and donors work towards peace, stability, and a hopeful return to the prosperity of the past.

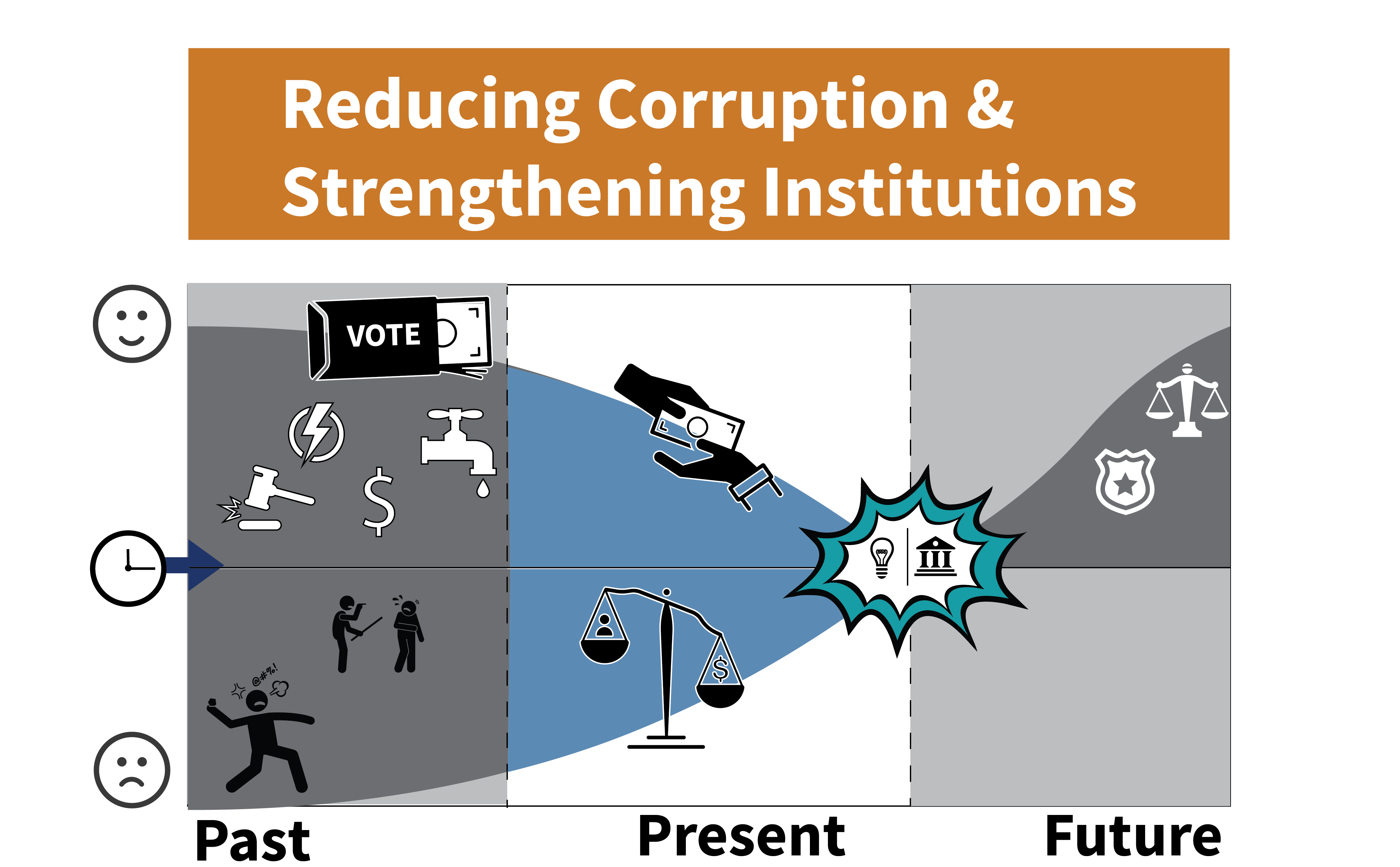

There is great disparity between the privileged class and non-privileged citizens. Those who wield wealth, power, and influence are able to reinforce their wealth and power, while influencing politics, the partitioning of services, and the justice system.

Through donor-funded programs and creative partnerships that seek to educate citizens and increase their perception of corruption, strengthen government systems to resist corruption, and foster a culture of accountability.

The playing-field is slowly leveled as government institutions become more accountable to the public, civic engagement increases, and citizens receive more equitable protections under the law, distribution of public services, and economic opportunities.